I came upon this fellow Beau Dick in a place where people are steeped in stories of soul travel and soul capture, and witchcraft, and that is the old way, they say, which just so happens to be relatively preserved one ferry ride beyond 'the last outpost.' At times, to my way of thinking, "it's the only way." Even with all this goodness to draw upon, the majority wear the yoke of modernity around their neck, so they eschew their own medicine, but Beau Dick was a man who set himself apart from modern beliefs.Beau Dick, Indigenous artist of the North West Pacific Coast tradition, was a leading proponent of the collective experience when it comes to builders and artisans cooperating on big projects. Beau saw a shared burden strongly reflecting the traditional life of Indigenous communities of the North West Pacific Coast.

"The time-line in the experience is all shared," he explained, about working on cultural projects. Beau was a man with strong connections to the coastal past, born in 1955 and raised in Kingcome Inlet, B.C. (an inlet flowing deep into the mainland coast) there to grow up with a lot of culturally-grounded individuals.

Beau lived his first few years surrounded by extended family including Elders, uncles and aunts, and others who maintained the society of Big House Potlatch culture. They lived in personal contact with pristine surroundings of Kingcome Inlet, rooted in history, sustained by hard work and preserving a once-thriving culture by manufacturing various arts and crafts.

Beau's early years were spent fully immersed in Kwakwala, the language of the nation. Beau sat amongst carvers, father, grandfather, and uncles, and listened to histories, legends, laws, jurisdiction, in Kwakwala, and learned the way things came to pass. Beau became vigilant about maintaining and passing along that knowledge for the rest of his life.

Beau was still young when the family took him to Vancouver to get serious book learning. He described a culture shock that lasted for a few adolescent years. Upon return to the Pacific North West the family was separated from Kingcome Inlet and Beau settled in Alert Bay, B.C., on Cormorant Island. His early life lessons began to percolate.

Beau was a hereditary chief in the Kwakwaka’wakw society called Homatsa. It is the warrior society in coastal clans holding jurisdiction in this part of the world.

In 2009, Beau was at a culture camp on Yukusem (Hanson Island), a semi-remote site 15 km south of Alert Bay accessed by boat. It was an informal project supported by a lot of volunteers from the beginning of July through the month of August that year.

The island’s other occupants include the year-round Cultrally Modified Tree anthropology study area in the island's heights occupied by David Garrick. Also, Orcalab whale research station occupies the south-east corner; and a logging license is held over 70 hectares on the north east side around Dong Chong Bay.

International kayak tours stopped beside the Yukusem culture camp at a lightly used campground to breath in the surroundings of Deep Bay. By the time tourist season arrived the Yukusem Culture Camp was in full bloom offering lessons to adventurous world travellers.

The culture camp on Yukusem was the brainchild of Beau Dick and the product of many hands. "It's a lot of teaching, cajoling, and inspiring, and convincing people the way forward is found by going through phases of knowing the past," explained Beau, willing and able to describe his extraordinary connections to the coastal past. Beau had worked with carvers of international reknown over the course of his life, Bill Reid included.

Beau became a world-recognized carver of the Kwakwaka'wakw tradition and had the right to carve a Haida coat of arms and other styles because of his bloodlines from Tongass, Alaska. His great-grandmother was a high-ranking hereditary chief of the Tlingit and married a Hudson's Bay Factor who took her to Port Rupert, north end of Vancouver Island.

Oolican is an important fish to Indigenous people of the Pacific North West, a fish people use for many purposes, dietary and often healing. The oil is something they call 'gweena' and those of coastal bloodlines often have a bottle of oolican grease. "My grandmother inherited the right to first harvest of the oolican up Kingcome Inlet," said Beau, one balmy afternoon in the centre of the culture camp on Yukusem. "My great grandfather had inherited the right to 'first fish' from this river because his great grandfather brought the oolican to Kingcome Inlet."

Brought the oolican to Kingcome Inlet? Beau's ancestor took two canoes out to sea and paddled to Bella Coola. Once there he obtained oolican fry and eggs which he carried in his second canoe and returned south (and east up the distinctively remote Kingcome Inlet) to seed the river with oolican. That gave family rights to the first fruits in perpetuity, a valuable asset. The claim is recognized in a large copper in Beau's possession as the physical testament.

Beau recounted stories passed down generations in relation to first contact with Europeans on the Pacific North West coast. One of these stories described the fate of the first domesticated cat, another, the chiefs reaction to the rum custom of the British Navy.

The Spanish sailed up the Pacific North West coast and explored the islands and archipelago as early as the mid-1500s. But the domestic cat made its first appearance at a Kwakwaka’wakw ville in the Pacific North West in the mid-1700s when the Spanish landed inside the Kwakwaka'wakw nation to begin conducting business.

This Kwakwaka'wakw nation of houses, clans, and villages occupies the mainland, several archipelago islands, and the top of Vancouver Island on both sides. When the Spanish sailed up to one of the well-populated villes they were immediately visited by the chief who greeted the ship’s captain with a cordial welcome to the Kwakwaka'wakw nation. At this first meeting the chief saw a cat capering onboard the Spanish ship.

The Kwakwaka'wakw chief was enthralled with the creature and the animal was brought before the chief for closer inspection. After playing with the cat the chief believed he had received possession of it.

Beau ascribes the captain’s devotion to his pet as enormous, and the captain of the Spanish ship refused to relinquish the cat. A couple of intrigues later, and the Kwakwaka'wakw chief was in full possession of the cat.

The infuriated captain of the Spanish ship soon unleashed a furious cannonade on the shore at the Kwakwaka’wakw community blowing apart war-canoes parked on the beach in front of the bighouses. Canoes were never in short supply in a Kwakwaka'wakw community and a few minutes later a flotilla coursed toward the Spanish ship.

The Kwakwaka'wakw surrounded the Spanish ship and returned the cannon balls. They demanded the Spanish perform this excellent feat again. They were not, however, returning the cat.

The Spanish sailed away and left the chief in possession of the curious animal and he announced a special event to be held in his bighouse. Soon a gathering of chiefs and clan members was assembled and the stage was set to unveil the cat.

The chief reached into a large cedar basket and grabbed the terrified cat and threw it some distance against a wooden post where it stuck. Everybody oh'd and ah'd while the cat did a couple of frantic loops and took off never to be seen again.

The Spanish spent a number of years exploring and mapping the Kwakwaka'wakw nation, said Beau. They left the territory with a legacy of sketches of people, villages, ship’s log entries, and a few Spanish place-names.

Soon the Spanish were usurped by the British who brought something other than a cat. Beau said the British Navy began snooping around the territory occasionally gunning the Spaniards out of the region and often stopping at houses of the chiefs of Kwakwaka'wakw communities.

The British had a custom of ending each occasion with the protocol of a shot of rum. At first the chiefs were kind of 'taken' but not all were happy with the custom and some were offended by the British insistence at imposing the bitter tasting liquid on these special occasions. Indeed a large argument ensued among the chiefs about whether to allow the British to stay. The argument that prevailed was, "Ah, let them stay. What harm can it do?"

"Lineage is the most important part of our social structure," explained Beau. On Yukusem, conversation was supported by a chorus of nature, birds, crickets, frogs. "Talk about jurisdiction, I can describe the great divide. The Hudson's Bay Company conducted a slaughter of Haida people in the mid-1800s with poisoned blankets at the same time as the upper classes of England were amusing themselves by eating mummies," the remains of dead Egyptians.

The efforts of ‘blanket merchants’ failed to kill off the coastal people and small pockets of culture and Potlatch law continued to exist in tiny enclaves like Kingcome Inlet. By the 1930s the Kwakwaka’wakw were repeatedly jailed for Potlatches in hidden Big House societies, "My people were real rebellious. The Kwakwaka’wakw were tenacious about keeping their ways alive."

The rebellion would take dramatic form at times, for instance, when Beau's uncle Jimmy Dawson raised a totem pole for King George V, "as a celebration of the king’s coronation. And at the time of the event, the question was simple, What are the authorities going to do about that? Nothing. There was nothing they could do."

Beau credits his forefathers for being adept at the art of deception and using double entendre to send a message, "The pole stands beside the Anglican Church in Alert Bay today," he said, "along with the commemoration plaque for the English king."

Those days and weeks spent with Beau at Yukusem were highly instructive. I had visited the area before, and left and did not return for a few years. When I did, I found myself living like Bakwis, wildman of the woods, and perhaps I had become one of those. I stayed with a politically astute fellow named George, on Atli Road. Atli means bush or forest. George explained how the community exists under a communications embargo, what George called 'Coercion by economic sanction.'

I stayed a few nights with George, which dragged into a couple of weeks but repeated visitations by a few party animals wore me down. That's when I took another refuge with Beau Dick, in his house/carving studio/classroom/crossroads on the beach. Instead of night owls and other faeries, I hung around artisans and culture mavins. They continue to carve a language that says a couple of things to God in statements that have no meaning to anybody but Him anymore. So the statements are not exactly meaningless, but who knows the mind of God?

Well, there is one fellow out in the territory possessing some deep insight. The study of Culturally Modified Trees (CMTs) is the study of human beings organized around rainforest resources. What David Garrick, anthropologist, uncovered on Hanson Island (Yukusem) is the "transgenerational" management of forests by Indigenous people at the northern entrance to the Inside Passage.

This transgenerational management of forests was comprised of a complex arrangement of separate preserves under jurisdiction managed to both maximize and distribute essential resources. Social groups conducted specialized horticulture within groves of cedar on Yukusem’s 16 sq. km..

One aspect of the cultivation involved shaping cedar trees to produce tree bark in surplus while keeping the tree alive. They maximized cedar bark production stripping bark lengthwise up a trunk, thus allowing the tree to heal, thrive, and produce surplus bark. This strategy illustrates how cedar bark was a staple. Cedar bark was produced for an apparently endless array of manufactured goods. The rule was to cultivate cedars into giant sources of raw material for production of manufactured goods. In the transgeneration aspect, people of Yukusem 1,350 years ago cultivated a grove of trees to furnish Beau Dick with raw material in 2009.

Beau's Alert Bay studio involves a lot of interaction with local artists and carvers. A couple of these artists are devoted to Jesus. I might have tried to explain that I do, really, believe in Jesus. In order to steal this continent and launch a genocide they needed an inside job. That's how Jesus enters. He's the inside job.

Beau finds this line of reason amusing but my friendship with Wayne becomes elusive at the point when I am demonstrating heresies in a couple short, disturbing arguments. I rarely feel friendship in the morning hours until Wayne has had a gallon of coffee to derail his brain.

There is considerable interaction and especially rancorous moment during which I say things like, "I cannot get divinely inspired by a manager of a sheep abattoir," and Wayne replies about ghosts not supposing to have voices, while painting messages in all kinds of uninterpreted ways, language being used like a sharp detailing knife. Wayne reiterates I should inhabit the vicinity like a ghost.

During the drunk and smoke fuelled evenings up Atim Road, George called the Kwakwaka'wakw communities part of a League of Autonomous Collectives, formerly tight competitive, industrious organizations oriented to acquire by trade.

"And warfare," according to Beau, who informs me the organization was codified in Wakashan, composed in a legal motif hieroglyphically rendered, a language emanating coast-wide (which Wayne describes as "the longest coast-line in the world.")

The archipelago was home to people cultivating immense riches. They had growing populations, educated in craftsmanship like house building, canoe-making, weaving, carving, resource extraction, a group of nations thriving on abundance.

I am tempted to suggest the hieroglyphic language carved on poles, painted on house fronts, sewn into chilkat blankets, was on the verge of a continental breakout. "There is a strong desire to build something but an awareness that others have standards which may be too high to be met by the revival of a cultural experience," Beau explained.

The culture camp on Yukusem had been a collective of builders and artisans volunteering to live rustic, practically remote, and, says Beau, "The question was, are you a camper? Camping is by definition a completely interdependent experience. The burden is shared and activities are shared. The time-line in the experience is all shared."

Beau returns to story-telling, "The Bella Coolas were primarily Salishan people who over a period of time had occupied the area up Burke Channel, halfway along the B.C. Pacific coast, and after this came a period of encroachment upon the Kwakwaka’wakw territory," Beau explained, for Bella Coolas had long been envious of Kingcome Inlet resources, he said.

It was therefore predictable to Homatsa society a large party of Bella Coolans would arrive at the entrance to the territory at Gilford Island. The arrival of the lead Bella Coolan party was made in peace and bearing gifts, a disarming presentation drawing the Homatsa society into a lull, while a second party descended and destroyed the Gilford Island settlement and left many heads on sticks and took Kwakwaka’wakw women away to Bella Coola.

Beau continued, "These women retained their names and their titles, but only gradually did the truth about their origins begin to emerge." He explained family status in a coastal nation is paramount and hierarchy composing the society is immutable. "Eventually the elevated status of those women and their offspring emerged and altered the face of a Salishan principality."

Mamalillikullu and the Haida were accustomed to crossing the Kwakwaka’wakw waters every year during the summer to conduct trade missions with the Cowichan and Salishan nations. When Hudson Bay Company arrived and a fort was established at Fort Rupert the HBC immediately set about usurping Kwakwaka’wakw jurisdiction. This made peace untenable, said Beau, once Haida traders arrived at Fort Rupert and bypassed traditional protocol of stopping at the clanhouses of Kwakwaka’wakw chiefs. Instead they opted to gather around the HBC fort and ignore customary exchanges with Kwakwaka’wakw.

In response to this diplomatic snub Kwakwaka’wakw messengers spread word and soon Homatsa society arranged their own reception. The Haida were intercepted as they continued a southward journey through the Inside Passage. The interception occurred at modern day Kelsey Bay deep in the present day Johnstone Strait. It was here they were surrounded and slaughtered. The heads of the Haida chiefs were taken back to Fort Rupert to the women who stood on the beach holding out their aprons.

As the Kwakwaka’wakw rowed past they tossed the heads ashore, said Beau, onto the aprons of the women. The head of one Haida chief tore through the apron of his wife and rolled along the beach, and the story is told, he was still trying to get away from the Kwakwaka’wakw.

Language was extinguished in an onslaught of flames and reeducation. The systemic racism remains intact via modern schools. Dissidents are held inside internment camps and gulag reservations are filled with dissident elements of a remaining population, some of those governed by a re-constituted national identity expunging traditional values, others suffering the lash of authority but defying all descriptions of servitude.

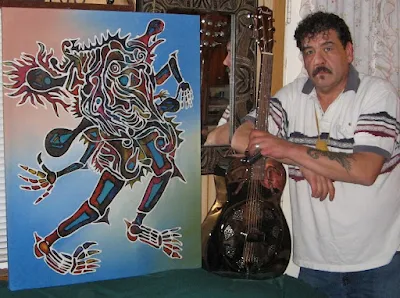

Friendships for me are illusive but people on this Indian Reservation come in waves to visit and work and confer with Beau Dick. It is a multi-user art studio, Wayne's, Marcus', Sean's, and tonight Thomas Bruce paints here. I once stayed at Beau Dick's two or three months a year previous. I have been here several times. I've been hanging around since the 90s. Several people are acquainted with me. Sean carves and paints a modern version which Beau Dick encourages as avant garde, and they are saleable pieces.

As I sit around, Sean tells me he is leaving shortly to spend Christmas in Port Hardy, a neighbouring town. Wayne inhabits the workplace daily but with the permanence of a sphinx. Beau Dick produces several pieces at a time, ruminates on new ones, uses a vast library and historical record in his designs. The library includes Beau Dick and Wayne's own knowledge orally transmitted and accompanied by images.

I am making my fifth, sixth, journey to the territory. It is now December 23. My activities this visit included scrapping with George's gang (testing my aptitude for listening), but Beau Dick and his immense Homatsa knowledge keeps the warcanoe on an even keel, his strength, and endless rounds of conversation in a circulating fashion in the studio, makes the stay worthwhile, such as when Wayne says, "There are six species of wolf on the north west coast. They can swim. They eat brains." I restrain myself from saying, "I guess you're safe."

On this Christmas Eve I am ending the visit to the Indian Reservation. Beau has been aloof my whole visit. This last evening was one of the rare occasions we are alone in the house. I am leaving in a few minutes. "I had a dream the other night and in this dream I was in Kingcome. I held a spear and several of us were holding spears. We had a big black cat in front of us. Eight of us circled around this cat and we weren't attacking. We were cornering the cat to put it in a cage."

"One night in the 1970s," I replied," I did a hallucinogenic drug, some organic mescaline, and 'transformed' into a puma. I had been injured the year before and the experience stuck with me, because, ya know, Beau, a wounded animal wants to kill every in sight."

Beau went to another room in the tiny house and came back with a t-shirt, smiled broadly, and he held it up, "This is you." It says, 'Ruined.' We laugh under a cloud of smoke. I leave a minute later to catch the last ferry of the night. It was the last time I ever saw Beau Dick. He was my friend. May he Rest In Peace.